Sometimes I imagine what the media’s typical coverage of disability might say if it was written about me—covering the two proms I went to with my girlfriend in high school, celebrating my ability to graduate from college after almost failing the second grade and spending most of my childhood in physical and occupational therapy, or eulogizing me after death as inspirational “in spite of” my disabilities.

Media centering on disability often falls into a dichotomy of disabled people seen strictly as objects of either inspiration (“Look at what they can do with a disability!”) or pity (“Look what they can’t do, and how much of a burden this is on their community”). Every time I see this, I’m reminded of how little my humanity means to some people. I’m not really a full person, but reduced to this dichotomy.

When it’s clear that a journalist doesn’t understand what it’s like to be a part of the disability community, reading their stories feels like a gut punch. And they might quote parents and caregivers as sources, but not even speak to a single disabled person.

As a journalist, it feels natural to me to include disability in my own work because I have lived experience. But when I started tackling wider disability issues and including a disability lens in my general reporting, I wondered, “How can I make sure I’m actively not causing harm to other disabled people, whose experiences of the world and ableism might be very different from mine?”

Here’s a list that I use every time I’m working on a story, whether it has a central tie to disability issues or not. This list is just a starting point, but this is a shift that we currently need in reporting and media—and I’d like to see journalists across all types of media get on board with making these changes in their own work.

- Reference the National Center on Disability Journalism’s language guide as a starting point, and continue to consult disabled people and disability rights organizations about inclusive, non-harmful language.

- If you’re in the position to hire a disabled writer for your project, choose to do that. Disabled Writers is an excellent resource where you can find writers, sensitivity readers, sources, and editors.

- Do thorough research in your reporting, and your due diligence. Read, listen to, or watch media created by and for people from the group you’re reporting on as part of your process.

- Understand established biases about the larger disability community, and any specific sub-communities you might be writing about. Think about how your story will differ from existing stereotypes and tropes, and what biases readers will bring to it.

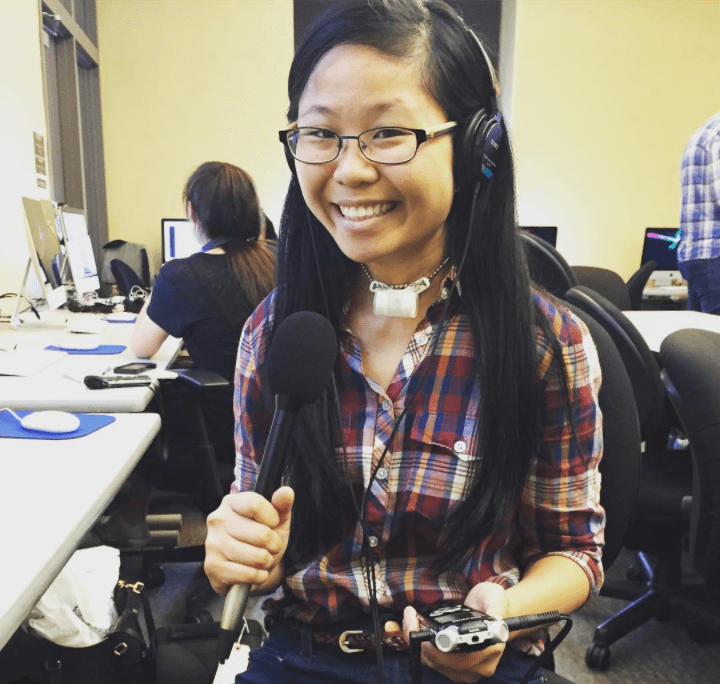

- Whenever possible, center the disability community in your work. Although you’re writing the story, let them take center stage in the work—quote them directly, and include them in photos and multimedia content where appropriate.

- If a story centers on one person or a group of people with disabilities, ask whether or not it would be newsworthy if those people were nondisabled.

- Consider the eight central news values (proximity, timeliness, prominence, magnitude, conflict, oddity, impact, and emotion), and ask yourself how much of the story is about emotion. Is the story meant to tug at readers’ heartstrings and positioned as a tearjerker or a feel-good piece? How much of that has to do with the story being about a disabled individual or group of disabled people?

- If the story is being covered because it’s inspiring or a feel-good piece, how does it fit into the overall canon of disability journalism? How does it compare with other stories about disability being covered (or not covered) by mainstream and independent media?

- Stay away from phrases like “wheelchair-bound,” “confined to a wheelchair,” or other language that positions wheelchairs and other mobility aids as prisons or traps.

- Actually interview disabled people. If you’re writing about a particular disability or a community of people with a condition, interview people from that community.

- Don’t assume that people want to cure their disabilities, and ask about and include disability pride in your reporting.

- Avoid language such as “suffering from” that creates a negative relationship between a person and their disability without confirming that is how an individual would like their disability described. Use neutral language whenever possible.

- Make sure your writing and multimedia coverage is accessible. Use alt text, offer detailed captions and image descriptions, create captions and transcripts for videos and audio content, allow users to magnify your web content, and avoid flashing animations.

- When appropriate, consider hiring a sensitivity reader or asking about a budget for sensitivity readers at your publication. A sensitivity reader is a person with a disability—ideally more than one person, and who share the specific disabilities and conditions you’re reporting on—who reads your work specifically for harmful and oppressive content. A sensitivity reader can help you parse through anything that might still need editing, such as problematic language or biased assumptions.

- Do you, as a journalist, include disability in every beat or section of a publication? Do you consider a disability lens for everything you write, including health and fitness, pop culture, lifestyle, sex and relationships, sports? Is your publication including disability in every section, across different types of stories?

- Go deeper than just this list. Every disabled person is an individual, so don’t make assumptions about how people would like to be identified (including preferences about naming their specific disability, or person-first versus identity-first language). Ask people to confirm their name, pronouns, and how they’d like you to identify—or not identify—their disability in the story.

About Rooted In Rights

Rooted in Rights exists to amplify the perspectives of the disability community. Blog posts and storyteller videos that we publish and content we re-share on social media do not necessarily reflect the opinions or values of Rooted in Rights nor indicate an endorsement of a program or service by Rooted in Rights. We respect and aim to reflect the diversity of opinions and experiences of the disability community. Rooted in Rights seeks to highlight discussions, not direct them. Learn more about Rooted In Rights