In the Stairwell, We Will Die

During my sophomore year of college, I wrote my will. That year was filled with trauma. I’d noticed a constant ache in my lower back that soon trickled down my legs and into my feet. They started to look like mountains with peaked arches and small toe pebbles that tucked beneath their surface. I skipped many classes so that I could visit neurosurgeons who eventually diagnosed me with a rare, non-fatal neurological condition called Tethered Cord Syndrome.

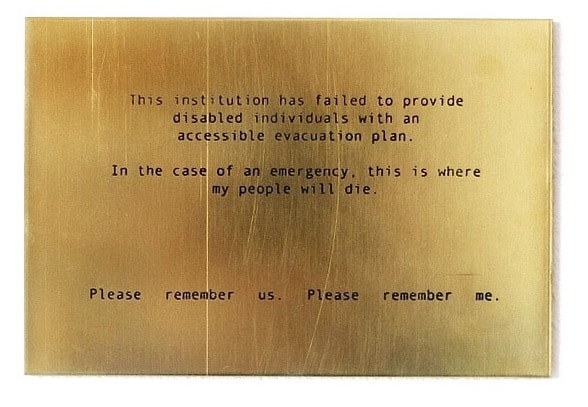

When my boyfriend learned that I was drafting my will with a lawyer, he panicked, thinking that my disability was the threat. I told him, “I am not afraid that my body will kill me. I am afraid that I will die at the hands of my inaccessible school.”

This fear wasn’t rooted in some anxious fantasy, but in the harsh reality faced by all disabled students. Like many institutions, my art school did not have an accessible fire escape plan. When I asked how I was supposed to carry my service dog, manual wheelchair, and my weak, wobbly legs down the concrete steps, I was told to wait patiently and they would try not to forget me. So, as instructed, I waited and watched as the able-bodied students rushed past me to safety. I spent this time contemplating my own death and the death of the one disabled professor who sat in the stairwell with me.

No one ever came to get us.

Throughout the rest of the school year, this fear was affirmed as I was persistently met with physical, cultural, and social barriers. Sometimes my wheelchair and I would get stuck in the bathroom stall. I’d pray someone would stumble upon the scene to help while also hoping no one found me stuck with my pants down and ankles pinned between the toilet and my wheelchair.

After critiques, where we spent four hours at a time giving constructive criticism about each other’s art, the Disabled and Black students would silently shuffle into my dorm room. We’d independently critique each other’s artworks because our in-class discussions were led by a white, non-disabled faculty member who bluntly said that our artwork celebrating our cultures would not make any sense to people in what they called the “real world.” When the elevator broke down, I was forced to miss classes because the school neglected to put a backup plan in place despite my pleas. As I turned to wheel out of the school, the security guard shouted, “Why don’t you just get up and walk?”

Every student experiences emotional and physical tolls in college: student debt, overbooked schedules, and fast-approaching deadlines. But everyday stress is amplified for the Disabled student who, on top of all that, also experiences hostile inaccessibility, ableism, and a lack of representation. They are expected to ignore their bodies’ needs in order to fulfill the ableist demands of their institution.

Because inaccessibility hindered my daily life, I spent most of my free time begging the administration for equal access. I felt like I was going to war with an opponent who refused to fight fair. Administration made little effort to address the inaccessibility that surged through the walls of the institution, claiming to be restricted by the school’s historic building status or lack of funding.

This forced the responsibility of accessibility and change onto the shoulders of disabled students. There were good professors who would let me leave early when they saw my health declining and others who would remove the chair from the desk before I arrived so that my wheelchair could smoothly slide in. They made the school year bearable but to settle for bearable is no way to thrive.

Occasionally, I’d win a battle like successfully getting a ramp, but it never outweighed the stark reality and overwhelming fear that consumed me: I could die here. Growing up my mother always said that I could endure pain simply by putting mind over matter. When I started to feel the emotional and physical toll of attending an inaccessible institution, I thought that maybe I wasn’t strong enough—in fact, it’s the system that’s broken.

A crucial way to fix our nation’s inaccessible school system is to share our experiences, to refuse to remain silent. We must amplify our stories because our rebellion disrupts the pattern. We must celebrate the rich values of disability art and culture and recognize that inaccessible colleges force out passionate disabled students who bring critical perspectives to an otherwise non-disabled discussion.

We must redefine our approach because the needs of disabled people are not “special,” our needs are human. At the bare minimum, disabled students deserve safe, accessible, and equal access to the education we’re guaranteed by law.

This upcoming school year I have decided to transfer to a new college. I do so begrudgingly, as I won’t be graduating from my dream school. But I try to remind myself that this dream school doesn’t even have a ramp to their stage for my graduation. They never expected me to survive there in the first place.

Oaklee Thiele (she/her) is a disability rights activist, public speaker, and protest artist whose work chronicles life from the disabled perspective and addresses systemic discrimination within academic and artistic institutions. She is the co-founder and head artist for the My Dearest Friends Project, an international art collaboration that archives, illustrates, and amplifies the stories of disabled individuals.

About Rooted In Rights

Rooted in Rights exists to amplify the perspectives of the disability community. Blog posts and storyteller videos that we publish and content we re-share on social media do not necessarily reflect the opinions or values of Rooted in Rights nor indicate an endorsement of a program or service by Rooted in Rights. We respect and aim to reflect the diversity of opinions and experiences of the disability community. Rooted in Rights seeks to highlight discussions, not direct them. Learn more about Rooted In Rights