When Do I Get to Say “Me, Too?”

I love the word “disabled” because it speaks to the heart of the matter: my ability to move freely through life is hampered. As an “invisibly” disabled, white-passing, biracial, queer femme, I wear my privileges like armor. Pretty masks queer. Class privilege obscures immigrant identity. My intact physical body hides a multiply broken, neuro-atypical brain that prevents me from functioning in a society that demands that I serve a function. Even so, no amount of hiding behind the so-called “invisibility” of my disabilities will erase the fact that I don’t possess the traits that this world is designed for. But I pretend that I do, because that’s what women do.

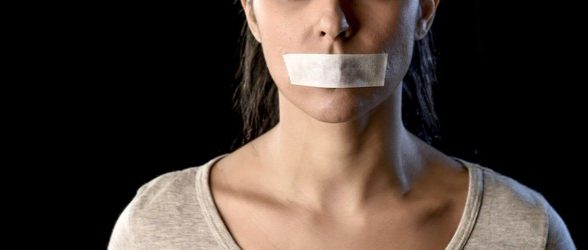

To speak out and say “me too” requires a voice to begin with – how do those of us with only half a voice contribute a full note to the conversation?

I had to let #MeToo slip by. I had too many naps to take, too many 12-Step meetings to attend. I couldn’t speak out against the teacher who harassed me because I am still a nobody in my field, and I couldn’t risk compromising my career. I was barely a week out of the hospital, reeling from the sedatives, when I met him for a beach date. It’s not strange that we’re meeting at a beach, right? It’s summer. So I stretched out on a sarong in a one-piece, feeling ashamed of my chunky thighs puffed up from food abuse. I felt his stare on my bare skin, but I ignored the knot in my stomach. I needed support. He was my teacher.

He sent me kissy emojis later. My head still foggy, I brushed aside my discomfort and rationalized that he was eccentric. He was blowing kisses as a father might, I figured. He piled the attention on as the weeks passed, until it came: the admission. “I have a crush on you,” he said. “I hope you don’t mind me saying so, given the #metoo movement.”

“The fact that you’re citing the #metoo movement should serve as a clue that this is inappropriate, don’t you think?”

“We’re both adults,” came the defense. Next was the harassment. The boundary pushback. I tried polite. I tried firm. Then I blocked him. And I let the incident slip away because I had no money and was completing my disability application while fighting a laundry list of mental illnesses. If I was somebody, I’d expose him. But I’m nobody, so I walk away. When you’re disabled and disenfranchised, you often end up being nobody. The odd dog will come by and pee on you, because he can get away with it.

My voice has been muffled by the very oppressors that we try to speak out against when we say, “Me too.” My “me too” comes out garbled, if at all. It’s usually too busy fighting for its survival to speak out against the predators that have been cornering me since I was a girl.

My story comes out fragmented the way my possibilities are interrupted. Invisible means I don’t always get to be a “me.” The “too” takes courage when my insistence already invites retaliation. To piece together a “me too” might require more of me than there is to go around.

My teacher got away with his harassment, like others did before him. But it’s nice to be able to raise my hand and say, “Me too,” in whatever way I can.

About Rooted In Rights

Rooted in Rights exists to amplify the perspectives of the disability community. Blog posts and storyteller videos that we publish and content we re-share on social media do not necessarily reflect the opinions or values of Rooted in Rights nor indicate an endorsement of a program or service by Rooted in Rights. We respect and aim to reflect the diversity of opinions and experiences of the disability community. Rooted in Rights seeks to highlight discussions, not direct them. Learn more about Rooted In Rights