The Complexities of “Passing” as Nondisabled

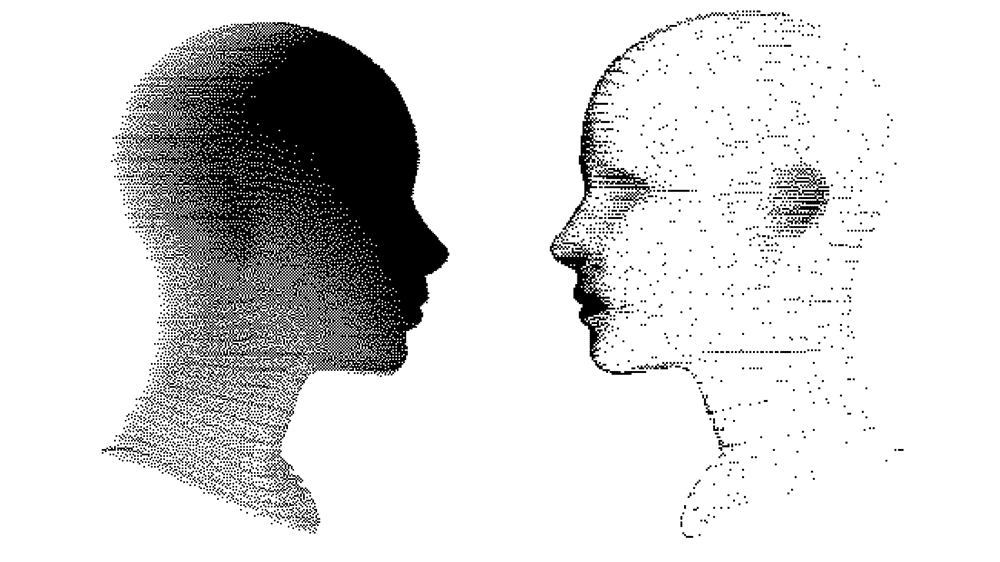

“Passing privilege” is a term used to describe what people of minority identities experience when they appear as though they’re not part of that minority group. It means you may not experience the same oppression and problems as others who are of that identity because you can be mistaken for the oppressor. In the disabled community it means that you don’t “look” disabled. Unfortunately, references to passing can also be a way for people within your community to insinuate you don’t belong there.

This usually applies to people with chronic illnesses and invisible illnesses and disabilities. It’s often implied that because you can “pass” as able-bodied, you don’t face the same challenges and therefore have an easier life than someone who is visibly disabled. People judge you solely by what they can see and decide that you don’t fit into their preconceived box of what “disabled” should look like.

The majority of my illnesses—lupus, arthritis, osteoporosis, dyspraxia, anxiety, depression and an undiagnosed reproductive issue—don’t have many physically visible symptoms. Having lived most of my life with invisible illnesses and disabilities, I know that it’s not always a privilege to not “look” disabled.

When we pass judgment on who gets to be considered disabled, we’re basically saying whose pain is believable, and that disabled and chronically ill people are only worthy of being believed if we “perform” our disability.

Not “looking” disabled has meant that I’ve been treated as though I’m lying about my illnesses. I’m used to teasing and jokes about my clumsiness by friends and family, but when people who are supposed to love and support me haven’t believed me, it’s quickly turned to bullying and belittling.

As I don’t display any physical symptoms, illnesses can be harder to diagnose. It took nine years for doctors to take my lupus symptoms seriously and respect that my mother wasn’t being “neurotic” and I a typical hypochondriac teen. I still experience doctors sneering at me and asking how I can possibly know something when I suggest a diagnosis, despite living in a sick body for 24 of my 31 years.

When I use accommodations designed for me whilst not appearing physically disabled, I’m often met with looks and sometimes hurtful comments from strangers. I’ve stopped sitting in the seats reserved for disabled people on the bus even though I struggle to walk further up the bus because I’d rather not face the abuse.

After a while, I started to internalize this and would try to hide my disability as much as possible. I put myself in dangerous situations to make others feel more comfortable. I will never do that again.

In a world that was not designed for disabled people and where the abled body is the cookie cutter, of course there are going to be privileges that come with not “looking” disabled. You may fit in more easily with your peers and you’re less likely to face discrimination and bullying because of your appearance. You won’t have to worry that you won’t be selected for a job because you appear to be disabled. When you date, you don’t have to worry that you’ll rejected based on visible signs of disability in a world of online dating that judges based on images first.

I’ve never been reduced to a wheelchair rather than a human. I’ve never been harmed in public by someone trying to push past me or push me out of the way. I’ve never been told that I’m a burden to my family and that they’d be better off without me.

I’m not denying that I hold a lot of privilege. I’m white, thin, do not live in poverty, am fairly well-educated, and English is my first language. Writing this essay made me look at my own unexamined privileges. Whilst I do struggle some days, on most days I can walk unaided. I’ve never struggled to enter a venue or find a seat somewhere because they’re not wheelchair accessible or don’t have spaces for wheelchair users.

So, where do we go from here? I think all disabled people need to examine their own biases and assess how they can be better advocates within their communities. There’s work that needs to be done both by people with visible and hidden disabilities to challenge stereotypical views of disability. And allies, as always, should educate themselves and challenge ableist behaviour if it’s safe.

It’s tough for all disabled people, full stop. That said, everyone’s experience of disability is different. You can have the exact same illnesses or disabilities as someone and still be on a different path. We must stop ableist comparisons of whose experiences are worse and who is more deserving of being recognized as “disabled.”

About Rooted In Rights

Rooted in Rights exists to amplify the perspectives of the disability community. Blog posts and storyteller videos that we publish and content we re-share on social media do not necessarily reflect the opinions or values of Rooted in Rights nor indicate an endorsement of a program or service by Rooted in Rights. We respect and aim to reflect the diversity of opinions and experiences of the disability community. Rooted in Rights seeks to highlight discussions, not direct them. Learn more about Rooted In Rights