Embracing My Queer, Disabled Identity

I realized I am not straight my junior year of college. I had a massive crush on my friend, a girl. I still liked guys, though, so I figured I was bisexual, or pansexual, or whatever you want to use to describe someone who is attracted to all genders. Let’s use queer.

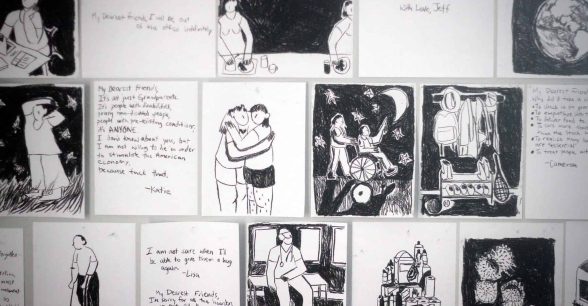

As I began to come out to people as queer, I started wrestling with another realization: some of the friends that I came out to did not see disability the way I did – as simply a way of being, complete and not in need of curing or fixing. And yet, they embraced my sexuality as just that – whole and beautiful and not wrong or less-than. Other people, I knew, would see things in the exact opposite way. They’d be on board with totally embracing my disability, but not my sexuality. How could this be?

Queer theory posits that “being normal requires thinking in only certain ways, feeling only certain things, and doing only certain things. And it punishes those who do not conform, such as those who do not look normal, or love the right kind of person, or value the important things” (Kumashiro, Against Common Sense). I learned about queer theory before I learned of my queerness, but I fell in love with the ideas immediately, felt home inside the words. While some people who identify as queer feel that being queer is bad and so try to show they are as “normal” as everyone else, others go against this, taking pride in their non-normalcy because normalcy is an oppressive ideal to live under. I recognized this struggle within myself and within the disability community – do I hide the more “disabled” parts of myself to try and pass as “normal,” or am I proud of these characteristics that so clearly set me apart, recognizing that it’s not me who is damaged, but the narrow constraints of what is considered beautiful, celebratory, good?

I understand the danger of conflating two minority groups with one another. But I’d like to ask: If putting disability and sexuality side by side makes you uncomfortable, why do you think that is? Is one of these things shadowed with inherent negativity in your mind and thus you don’t like the other being compared to it? If they are both not things we choose, but rather parts of our identity that we have no control over (although it’s true in some cases that we can choose to embrace or hide these parts of ourselves), how are they, at their core, really that different?

Sometimes I use “not straight” to describe myself, especially when I feel like the listener will not understand the full meaning of “queer.” But queer is what I prefer to use because it is, ultimately, what I am. In Fenton Johnson’s essay, “Future of Queer,” he sets forth that “What defines queer is not what one does in bed but one’s stance towards…the status quo.” To me this doesn’t mean the stereotypical anti-establishment beliefs or radicalism we see of taking to the streets to protest and march, although that could also fall under this umbrella. To me it means being willing to look at reality from a completely new perspective, a perspective that challenges you and makes you uncomfortable. Queer means embracing all of the aspects of myself – both disability and sexuality – that I have been told not to be proud of.

About Rooted In Rights

Rooted in Rights exists to amplify the perspectives of the disability community. Blog posts and storyteller videos that we publish and content we re-share on social media do not necessarily reflect the opinions or values of Rooted in Rights nor indicate an endorsement of a program or service by Rooted in Rights. We respect and aim to reflect the diversity of opinions and experiences of the disability community. Rooted in Rights seeks to highlight discussions, not direct them. Learn more about Rooted In Rights