May is Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome Awareness Month. Here’s What You Should Know.

When I tell people I have Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS), they usually give me a blank stare or reply, “What does that mean?” Answering doesn’t clear up any of their questions, and it actually creates more: How did I get EDS? Have I always had it? What does it look like in my daily life? Will it get worse as I get older, or is there a cure?

The Ehlers-Danlos syndromes are a group of genetic connective tissue disorders that are separated into thirteen subtypes. It’s considered to be rare and most people have never even heard of it, so they don’t have a conception of what it means to live with it.

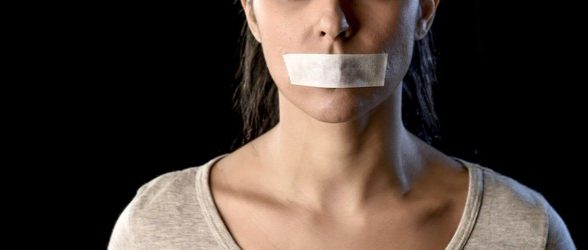

Many people with rare disabilities (and disabilities that are common but don’t have high public awareness) have to become expert self-advocates. We’re constantly in a position of educating people around us.

“I’ve had to become my own doctor, my own personal scientist, to get anything done,” says Annie Segarra, a YouTuber, writer, and artist who shares her experiences as a disabled queer woman of color. “It took years of pleading to be tested for EDS before I actually was.”

Kelsey Golden, a mother of four living in Omaha, Nebraska, says that she didn’t connect the dots to EDS until she saw it on an episode of Grey’s Anatomy. She spent eight months researching EDS and approached her physician with her medical history, diagnostic criteria, and case studies. He was skeptical at first, but her evidence quickly convinced him and she was diagnosed two weeks later.

People with rare conditions often spend a long period of time being undiagnosed. “I wasn’t diagnosed until just this year, at age 27, although I’ve had symptoms and have been looking for answers for my entire life,” says Courtney, a writer living in Arizona who has EDS and chronic Lyme. “I have a really classic case of EDS—I check off every symptom on a checklist—so it would be such a simple diagnosis if doctors were familiar with it.”

Since we’re waiting longer for diagnoses and doctors are less likely to be familiar with our conditions, we also don’t get a lot of the treatment and self-care tips that people with common disabilities (like diabetes) might get at an annual physical. I spent my childhood undiagnosed, so I never knew that I was better off not stretching out my hypermobile joints or contorting my body into odd positions. It was comfortable for me to position my body in ways that looked strange to my friends, and I didn’t realize I could be adding to chronic pain and connective tissue erosion down the line.

“I feel a little heartbroken when I think about the possible elements of my condition I could have prevented if I had known what I had earlier on and the only way that could’ve happened would’ve been through widespread awareness,” says Annie.

Aliska Shah, a queer South Asian writer and artist, was a professional swimmer for nine years, but was always injury prone because of her hypermobile EDS. Every couple months or so, she’d visit a physiotherapist, where she’d be told to stretch more often—which is actually counterproductive for people with hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos. “I live in a community where no one has heard of my condition, not even the doctors (I was diagnosed abroad), and I’m in a position where I have to constantly justify my reasons for quitting a promising professional career in swimming,” says Aliska.

In addition to advocating for ourselves at the doctor’s office, people with EDS often have to educate everyone in our lives, whether we’re in a social setting or a professional one.

While the reality is that people’s perceptions of common and widely known disabilities is often skewed and rooted in stereotypes, I often wish that more people had a basic understanding of EDS, because I’d at least have something to work from.

One basic but impactful thing people in my life can do is research what it’s like to have Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, ideally not only from a medical perspective but also by reading, watching, and listening to work by people with EDS (like Annie Segarra’s YouTube channel). When I find out that a friend has a disability or chronic condition, I’ll usually do research on my own and also invite them to tell me how it impacts their life if they’re comfortable. I make a point to remind them it’s not their job to educate me, but that I’d like to understand what accessibility means for them so I can be aware when we’re making plans.

Courtney says, “When I was first diagnosed, I mentioned it to a friend. We got off topic and didn’t talk too much more about it, but the next day he came up to me and said, ‘Hey, I read a little bit about EDS after you mentioned it. It sounds like it can be really rough! Let me know if I can ever help with anything.’ It was so simple and so appreciated.”

Awareness and education also helps significantly with myths about what it looks like to have a disability. “You would not believe how often I’ve been yelled at in parking lots or elevators for “being lazy” or “using my grandma’s parking pass,” because I “look perfectly healthy” (which is usually code for young),” explains Olivia Cline, a professor and editor living with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and several other comorbidities in North Carolina. “I once had to actually take my shirt off in a parking lot to show the person berating me all my tubes and lines and scars.”

The best thing you can do if you have someone in your life with a disability—even if it’s not rare and you think you have a lot of common knowledge about is—is to not make assumptions. Do some research on your own. Read about what it’s like from first hand perspectives and other people who live with it. If you’re comfortable, ask that person to tell you a little about it, and then don’t interrupt them, don’t offer them suggestions for treatment or a cure, and just listen.

About Rooted In Rights

Rooted in Rights exists to amplify the perspectives of the disability community. Blog posts and storyteller videos that we publish and content we re-share on social media do not necessarily reflect the opinions or values of Rooted in Rights nor indicate an endorsement of a program or service by Rooted in Rights. We respect and aim to reflect the diversity of opinions and experiences of the disability community. Rooted in Rights seeks to highlight discussions, not direct them. Learn more about Rooted In Rights